“You Need to Check Out This Song!”

An Investigation of Why We Share Music and Who Tends to Share

** NOTE TO READERS ** : What follows is my final project from a class I took my junior year (2016) at Harvard, titled “Music and the Mind”. Yes — such courses exist at Harvard; some of my other favorites included “California in the ’60s”, “Impression Management and Social Influence”, “Money, Markets, and Morals,” and beyond... The below is the text I turned in so please excuse any typos and/or histrionic, college-style writing. I also added some graphics and hyperlinks to spice up your reading experience. I’m sharing this now because (1) it may relate to an upcoming edition of my Content List series and (2) it’s an intriguing topic in general...

INTRODUCTION

I. Inspiration and Overview

Music is fascinating. It provides a soundtrack to our lives: songs permeate into all aspects and dimensions of our existence, from our most celebratory triumphs to our most melancholy sorrows, and everything in between. Music can not only convey emotion by smothering listeners in a vast sea of aural sensation — it can also elicit emotion and fasten itself to memories, making them more vivid upon recall (Sculkin & Raglan, 2014). In a way, music is its own language: it possesses syntactical structure and artfully communicates meaning, arguably, in a more profound, nuanced way than spoken or written parlance. Because songs are so adept at communicating feelings, they also function as a vehicle for socialization — especially since humans are definitively social creatures. Interacting collectively with music satisfies the “intrinsic human desire” to share experiences, activities, and emotions (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010).

Music can not only *convey* emotion by smothering listeners in a sea of aural sensation — it can also *elicit* emotion and fasten itself to memories, making them more vivid upon recall.

If an individual comes upon a new song, or digs up an undiscovered gem from decades past, that person might experience an ineffable urge to share that song so that others can experience the euphoria — or sadness, or nostalgia, or excitement — it evokes in them. It is almost as if the songs one finds are akin to infectious viruses, and one feels a pervasive desire, as the proverbial patient zero, to spread the contagion. At least, that is the case with me, a devout music enthusiast. To say I am ‘passionate’ about music would be an understatement — I live and breathe it, and it accompanies me throughout all my days and nights. A few years ago, in 2013, I wrote an article for an online music-centric publication called Cuepoint at Medium, titled, “I Heart EDM, So What?” The purpose of that piece was to explain how my generation discovers, consumes, and shares the burgeoning electronic music genre. Since I began analyzing the potent social effects music has, I realized I had stumbled upon a big (and apparently unstudied) psychological phenomenon: why do individuals “revel in the glory” of discovering a song and introducing it to their peers (Shecter, 2013)? Furthermore, what commonalities exist amongst people like me who possess this proclivity and incessant desire to share the songs they find?

Those are the questions I seek to answer in this paper. After explaining the ever-evolving dynamic of music sharing, I will first attempt to tackle the “why” component (i.e. different contributory motivations for why we share songs) then expound upon some potentially overlapping personality characteristics of habitual sharers. Next, I present an experimental paradigm to evaluate the relationship between relevant traits — namely, extroversion, competitiveness, and generosity — and how individuals derive emotion from sharing songs. I hypothesize that higher levels of each characteristic lead to (a) an increased desire to share songs, (b) a greater sense of ownership and personal identification with shared songs, and (c) greater happiness/sadness response derivation, contingent on peer response.

II. Changing Nature of Music Consumption: Ubiquity of Sharing

In my Cuepoint article (2013), I conjectured that the phenomenon of sharing songs is likely as old as replayable music itself. I maintain that stance, yet the evolution of the ways in which we consume music has greatly impacted and improved its share-ability (Albright, 2015). In the century and a half since Edison invented the phonograph, music has gone through about a half-dozen de-facto media of interaction. First there were shellac cylinders and disks engraved for use with the phonographs: these were clunky, low-fidelity, and short-lived.

Then came the radio revolution in the early 20th century and the popularization of vinyl following World War II — both of which constituted improvements in portability and clarity. The cassette tape was invented by Phillips in the late ’50s yet did not become utilized en masse until the late ’70s, thanks in part to Sony releasing their Walkman. Compact discs (CDs), which were developed in the ’80s, occupied the consumption marketplace alongside cassettes until the late ’90s when tapes fell out of vogue. At the turn of the century came perhaps the most crucial advent in the share-ability of music: its digitization in the form MP3s. Not only did MP3s allow users to upload and share songs on the Internet — it also gave users the ability to carry hundreds, if not thousands, of hand-picked tracks via iPods and other similar devices. Today’s consumption relies almost entirely on streaming — services like Napster, Pandora, Spotify, Apple Music, and SoundCloud — which expands users’ accessible music library, quite literally, to infinity and beyond (Albright, 2015).

It is necessary, before delving deeply into the psychological discourse, for one to comprehend the dynamic, ever-evolving mechanisms of music consumption and sharing. Music interaction is undergoing a constant metamorphosis and is now both insanely portable and highly customize-able: these two elements make songs highly conducive to sharing with peers. There are, thanks to these technological advances, countless instances in everyday life during which disseminating a newly-discovered track could occur: sharing an earbud with a friend while walking down a middle school hallway; during employees’ lunch break on Wall Street, cueing up a shared playlist for a group workout; late-night unwinding with roommates after an evening in the library; etc. Moreover, those with whom individuals share music are not restrictively friends: studies have shown that music is the most common conversational topic amongst strangers trying to get acquainted (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006).

Music interaction is undergoing a constant metamorphosis and is now both insanely portable and highly customize-able: these two elements make songs highly conducive to sharing with peers.

Although many of these now-popular streaming programs have artificial intelligence “taste algorithms” to select songs for us based on our listening history, there exists a unique feeling when another person introduces the song to us — a “human curation” element that is, to many, imperative and irreplaceable in their process of musical discovery (Popper, 2015). The takeaway from this subsection is this: music sharing has reached the point of ubiquity, thanks primarily to the current technological landscape of music consumption. Music is more accessible and share-able than ever, thus examining this topic is undeniably relevant.

WHY? MOTIVATIONS TO SHARE

I. Bonding Through Beats: Pro-sociality, Synchrony, and Social Connection

There is a wealth of literature that discusses music’s remarkable ability to facilitate social behavior among humans. Music connects individuals across several different domains, acting as a sort of Swiss army knife for socialization, the formation of interpersonal bonds, and synchrony. These multifaceted phenomena arise at a young age, which suggests an evolutionary basis for sharing (and mutually responding to) music. Kirschner & Tomasello (2010) found that four-year-olds who engaged in joint musical activities displayed enhanced pro-social behavior with their peers, denoted by increases in spontaneous cooperative problem solving and helping, and stronger group cohesion. Many other studies have indicated that similar music tastes engender and fortify social bonds (Boer et al. 2011, Schäfer et al. 2014, Schulkin & Raglan, 2014).

Music connects individuals across several different domains, acting as a sort of Swiss army knife for socialization, the formation of interpersonal bonds, and synchrony.

One report posits two plausible mechanisms by which music triggers these striking effects on social bonding: (1) self-other merging, where songs trigger similar emotions and movements in listeners thereby creating psychological blurring of their identities and forming “at least transient bonds” among them; and (2) concurrent hormonal release — specifically, endorphins and oxytocin in the EOS system — that equalizes listeners’ moods, resulting in synchronization, mutual, positive social feelings, and the underpinning of interpersonal bonds (Tarr et al., 2014). It is likely a mixture of these two mechanisms that accounts for the bonding that arises, especially since self-other merging is less prevalent (though still possible) in large groups (Tarr et al., 2014). Synthesizing these findings, individuals who source and introduce a song that is enjoyed by a collective group likely perceive a stronger connection to each individual, compared to how other listeners feel connected with each other.

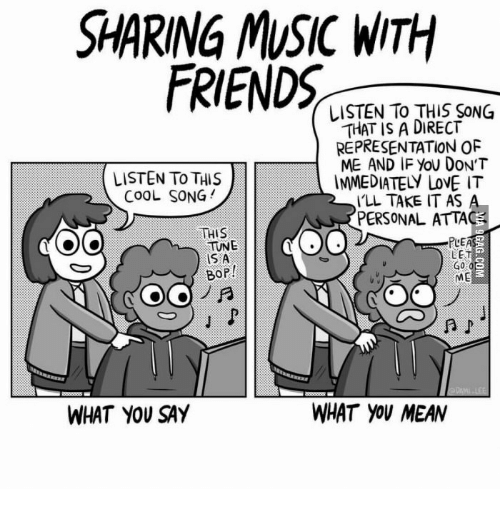

II. Revealing Ourselves Through Song Selection: Sense of Identity & Ownership

Sharing a hand-picked song can feel, in a way, cathartic. In the process of discovering or choosing a track to share, an individual undergoes an intrinsic exploration and a deepening of self-awareness — a strengthened comprehension of one’s (sometimes unknown) motivations, feelings, and behaviors (Bensimon & Amir, 2010). Why is it that I like this song, one may ponder, internally. Why does the song resonate so deeply with me? Having higher levels of self-awareness is not only beneficial for ourselves; it increases outward-directed compassion and mobilizes pro-social behaviors, like sharing (Lindsay & Creswell, 2014). As a consequence, individuals experience a strong personal identification with the songs they choose to share with peers (Bensimon and Amir, 2010). Stated eloquently, “individuals use their musical preferences to communicate information about their personalities to observers, [so] observers can use such information to form their impressions of others” (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006). By sharing a song with which we identify, by this logic, we are essentially sharing a piece of ourselves.

Additionally, many people — especially young adults — consider their music preferences much more revealing of their personalities than their taste for movies, TV shows, clothing, books, movies, or food (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006). These considerations may contribute to this “urge” to share the music we find: we want our friends and peers to understand us more deeply, to accept us. In addition to communicating personalities, music taste also acts as a “social badge” that reveals the values of the sharer (Boer et al. 2001). These theories hold true on the receiving end as well, as studies indicate that listeners have an “intuitive understanding” of the links between personality, values, and music preferences (Boer et al., 2001; Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006).

Many people — especially young adults — consider their music preferences much more revealing of their personalities than their taste for movies, TV shows, clothing, books, movies, or food.

Because individuals identify personally with the songs they choose to share — a sort of “musical audio-biography” effect (Bensimon and Amir, 2010) — it should come as no surprise that some may feel a sense of ownership over their selections. This may be puzzling in some ways since (in most cases) the sharer did not write or produce the song nor is he or she the only person on earth capable of accessing it (Shecter, 2013). That said, this perception of ownership is not entirely illogical and is actually somewhat intuitive. If the sharer feels a special connection to the song, that connection is somewhat diluted when the sharer learns that another friend has independently discovered the same track. Sharers may, alternatively want credit for their discovery among their friends: it is, after all, (essentially) their selection inciting those feelings that are shared by the group. Investigating the sense of ownership we feel over our music could be the subject of its own research paper; for this report, however, it is important to note it as a component of our motivation to share.

III. Deriving Happiness and Sadness Contingent on Peer Response

If one examines DJs or instrumentalists — the ultimate sharers of music — during a performance, it is evident that they derive immense pleasure and happiness from seeing the crowd react positively to their selections. Becoming “one with the crowd” is the goal of many DJs: bringing everyone together to the same social wavelength, leaping in euphoric unison to the beat of the endless song (Shecter, 2013). It is empowering and elating yet at the same time deeply connective: the performer is wholly invested in the music, the audience and how they respond. The crowd has a heartbeat, and it is the artist that provides the pulse.

In the case of professional DJs (more so DJs of yesteryear than the present) and other music fans, the process of discovery is lengthy, tedious, and methodical. Finding an undiscovered gem-of-a-track used to require hours of “cratedigging” through dusty old record stores (Iandoli, 2014), and many individuals today still adhere to these old-school practices. The digitization of music, as mentioned above, has resulted in the development of many taste algorithms and predictive software (Popper, 2015), yet finding a song worthy of sharing can still take hours of virtual sifting and listening — a modernized style of cratedigging. Witnessing people respond positively to a selection thus acts as a validation of the sharer’s efforts, and such a reaction induces happiness and pleasure in the sharer. Imagine, in addition to the euphoric DJ, a boyfriend rejoicing when he learns that his girlfriend enjoyed the mixtape he so carefully curated. Conversely, if listeners respond negatively and dislike a sharer’s selection, the sharer likely experiences a range of negative-valence emotions like sadness, regret, and embarrassment (Bensimon & Amir, 2010).

In addition to the above theorization, the happiness or sadness sharers derive may relate to the embedded personality in their selections. In other words, if peers do not like a shared song, the sharer may interpret that — consciously or subconsciously — as a rejection of his or her identity, and sadness (or regret or embarrassment) will ensue; the converse would occur if the peers respond encouragingly to the disseminated track (Bensimon & Amir, 2010).

WHO SHARES MUSIC? RELEVANT PERSONALITY CHARACTERISTICS

If there are others (like me) who have a penchant for sharing newly-discovered music — presumably, there are many — then there must exist some domain of shared personality characteristics. What are these traits? There is unfortunately a dearth of literature on the relationship between sharing behavior and personality attributes; thus, the subsequent analysis is based primarily on logical inference. The first, and probably most important, characteristic implicated in the music sharing phenomenon is extraversion. Ashton & Lee (2002) explain that there are two separate-yet-related facets of extraversion: (a) an underlying desire to interact socially and connect/bond with other individuals and (b) amplified reward sensitivity, an “incentive motivational state that facilitates and guides approach behavior to a goal.” Extraversion, in the case of music sharing, therefore must play a key role in an individual’s desire to share music and response from sharing music.

Another trait that likely influences both desire and response is competitiveness. Though it is not one of the “Big Five,” psychologists have developed a reliable metric to evaluate competitiveness dimensionally and relatively (Houston, 2002). Competitive individuals — by definition (Houston, 2002) — have insatiable desires to win in interpersonal situations. Thus, when it comes to music sharing, a positive peer reaction to a shared song would be considered a “win,” leading to a strong, positively-valence response from a competitive individual. These individuals would be more inclined to share in the future to get more such “wins,” especially in situations in which other people are competing for group approval of their music selections. Neurobiology is implicated here as well: the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is secreted during satisfaction and reward (i.e. victorious, pleasurable moments), has been associated with many music-related activities (Tarr et al., 2014).

A final potentially relevant characteristic is generosity, which relates directly to one’s willingness to give (Smith & Hill, 2009). More self-focused individuals would hoard their discoveries, reveling in their own emotions, and would have little desire to spread those feelings. Generous individuals, on the other hand, would be highly inclined to share their musical discoveries so others can experience the emotions conveyed and elicited by the songs.

PROPOSED STUDY

I. Explication of Variables & Hypotheses

One can extract several key variables from the above discussion. The experiment, overall, is intended to evaluate the impact of certain personality factors on individuals’ desire to share music.

To operationalize an experiment, it is important to define each variable and explain how each will be quantified. See the tables below for those specifications for three independent (explanatory) and five dependent (response) variables:

To assess the overall (composite) impact of extraversion, competitiveness, and generosity on the different responses from sharing, two composite (i.e. interactive) variables were developed. The “E.C.G. Score,” extraversion-competitiveness-generosity, is a mathematical composite of the scores from each of those surveys; the “Sharing Desire-Response Score” is a tantamount fusion of the five dependent variables.

I hypothesize that all independent variables will probably have sizeable, statistically meaningful impacts on the response variables. Stated differently, higher levels of each personality characteristic will lead to (a) an increased desire to share songs, (b) greater sense of ownership and personal identification with shared songs, and (c) greater happiness/sadness response derivation, contingent on peer response. Of the independent variables, extraversion will likely have the the strongest impact on the response variables, followed by the impact of generosity and then competitiveness. I also hypothesize a high correlation between the composite variables.

II. Methodology

Below, an ideal experimental paradigm is presented. It should be noted that this is but one of countless distinct ways to test the relationships between these important variables. Future studies ought to investigate different methodologies with the intent of further substantiation of these hypotheses.

III. Summary & Limitations

The above experiment analyzes subjects’ personalities, instructs them to find and present a song (to a group of trained actors), and evaluates the emotional/sensational states before and after song presentation. It is a straightforward paradigm to evaluate the strong (hypothesized) relationship between the variables.

One limitation of this design is the fact that the music sharing is planned rather than spontaneous. Real-world sharing is often impulsive, thus the emotional effects might be different leading into the presentation, and their volatility might be amplified during it. That said, this slight shortcoming should not skew the results too drastically; the hypotheses should still hold.

CONCLUSION: THE FUTURE OF MUSIC SHARING

As I anticipate the experiment would show, there is a powerful social impact from music sharing. These phenomena — the way music elicits such palpable cohesiveness among individuals, how sharing evokes such strong pro-sociality — seem flat-out magical. One might think that these effects are some of the seemingly intangible, immeasurable qualities of music, yet this experiment would add even further corroboration of its existence. Hopefully this experiment would motivate future studies in song sharing since it is quite unstudied in social psychology and musicology.

The mechanisms and trends by which we consume and share music will only evolve further as the years pass. Music discovery will likely become more programming based, impersonal (Popper, 2015), but as mentioned above there will always be a human aspect to discovery and curating songs. The best curators and sharers are the ones who engulf themselves in new music, seeing the trends in popularity before they arise. These individuals can be characterized as tastemakers: they are virtuosos in unearthing musical gems and disseminating them, the vehicles of the prevalence contagion. The future of sharing music will be more quantifiable; there ought to be a way to assess and evaluate our ability to discover, curate, and tastemake music.

Enter: Curate, my idea for an algorithm-based application that would do just that. Curate would track our first interactions with songs across all the applications we use to consume music: Spotify, Soundcloud, Apple Music, etc. At that moment of first interaction (or adding to your Curate portfolio), the algorithm logs the popularity of that track by documenting its number of listens, likes, re-posts, etc. The application would then track that song’s (and others’) performance over time, and the algorithm would develop a number (a “Curating”) that states one’s ability to foresee popular music. The score would be asymptotic from zero to 100: 1 = bad at forecasting musical trends, 50 = average ability to predict trends in popular music, 99 = expert connoisseur/trendsetter/tastemaker.

One’s Curate score would be displayed on their profile on all of these musical sites, thus serving as an indicator of one’s curating prowess. If (online or in a group of friends) an individual is deciding whose selection to trust and hear, he or she would be more inclined to hear tracks from a user with a higher Curating. Presumably, those with the highest ratings would be occupational tastemakers like record label owners, Diplo, Kanye West, John Mayer, etc (and, hopefully, people like me). Individuals would not be able to cheat the system if they happened to be at their computers the instant Beyonce uploaded a new, bound-for-popularity song: the algorithm would be smart, reactive, and sensitive.

Much of the data from this experiment would be useful incorporations to this algorithm and application (which is still purely in idea phase). The users of the app could take similar surveys to the subjects in this study, establishing their personality characteristics and response from sharing. More specifically, the interaction variables — E.C.G. Score and Sharing Desire-Response Score — are indicative metrics and ought to be implicated in the calculation of an individual’s Curating.

In short, this research — and others implicating music and the mind — provide psychological underpinnings for this app. Perhaps, in the future, Curate will be ubiquitous and synonymous with sharing not just music, but any new discovery (a new TV show or movie, restaurant, clothing brand, etc.).

References

Albright, D. (2015) The Evolution of Music Consumption: How We Got Here. Making Use Of Retrieved from:http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/the-evolution-of-music-consumption- how-we-got-here/

Ashton, M., & Lee, K. (2002) What is the Central Feature of Extraversion? Social Attention Versus Reward Sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 83. Retrieved from: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezp- prod1.hul.harvard.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e3c2d109–9b65–4304–811f- 5d1fea336a46%40sessionmgr106&vid=1&hid=109

Bensimon, M., & Amir, D. (2010) Sharing My Music with You: The Musical Presentation as a Tool for Exploring, Examining, and Enhancing Self-Awareness in a Group Setting. The Journal for Creative Behavior, Vol. 44. Retrieved from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/doi/10.1002/j.2162- 6057.2010.tb01336.x/abstract

Boer, D., et al. (2011) How Shared Preferences in Music Create Bonds Between People, Values as the Missing Link. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 37. Retrieved from: http://psp.sagepub.com/content/37/9/1159.full.pdf+html

Goldberg, L., et al. (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the Future of Public- Domain Personality Measures. Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 40. Retrieved from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0092656605000553/1-s2.0-S0092656605000553- main.pdf?_tid=6484b4a4–12e6–11e6–95db- 00000aacb35f&acdnat=1462469322_7226936624f1ea4b26f98282c871d6a9

Houston, J., et al. (2002) Revising the Competitiveness Index Using Factor Analysis. Psychological Reports, Vol. 90. Retrieved from: http://www.amsciepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.31

Iandoli, K. (2014) The Lost Art of Cratedigging. Medium. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/cuepoint/the-lost-art-of-cratedigging-4ed652643618#.rgbn2ig91

Kirschner, S., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Join music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4- year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, Vol. 31. Retrieved from: http://www.eva.mpg.de/documents/Elsevier/Kirschner_Joint_EvolHumBeh_2010_1552 719.pdf

Lee, R., et al. (2001) Social Connectedness, Dysfunctional Interpersonal Behavior, and Psychological Distress: Testing a Mediator Model. Journal of Cousneling Psychology, Vol. 48. Retrieved from: http://depts.washington.edu/uwcssc/sites/default/files/Social%20Connectedness%20Sc ale-Revised%20(SCS-R).pdf

Lindsay, E., & Creswell, J. (2014) Helping the self help others: self-affirmation increases self- compassion and pro-social behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, Vol 5. Retrieved from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00421/full

Popper, B. (2015) Tastemaker: How Spotify’s Discovery Weekly Cracked human curation at internet scale. The Verge. http://www.theverge.com/2015/9/30/9416579/spotify-discover- weekly-online-music-curation-interview

Rentfrow, P., & Gosling, S. (2006) Message in a Ballad: The Role of Music Preferences in Interpersonal Perception. Psychological Science, Vol 17. Retrieved from: http://pss.sagepub.com/content/17/3/236.short

Schäfer, T., et al. (2013) The psychological functions of music listening. Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 4, Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3741536/

Schulkin, J., & Raglan, G. (2014) The evolution of music and human social capacity. Frontiers in Neuroscience, Vol. 17. Retrieved from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnins.2014.00292/full

Shecter, J. (2013) I Heart EDM, So What? Medium. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/cuepoint/i-heart-edm-so-what-6e4ee7270f98

Smith, C., & Hill, J. (2009) Toward the Measurement of Interpersonal Generosity: An IG Scale Conceptualized, Tested, and Validated. Retrieved from: http://generosityresearch.nd.edu/assets/13798/ig_paper_smith_hill_rev.pdf

Tarr, B., et al. (2014) Music and social bonding: “self-other” merging and neurohormonal mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 5. Retrieved from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01096/full#B37

Vol. 4, Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3741536/